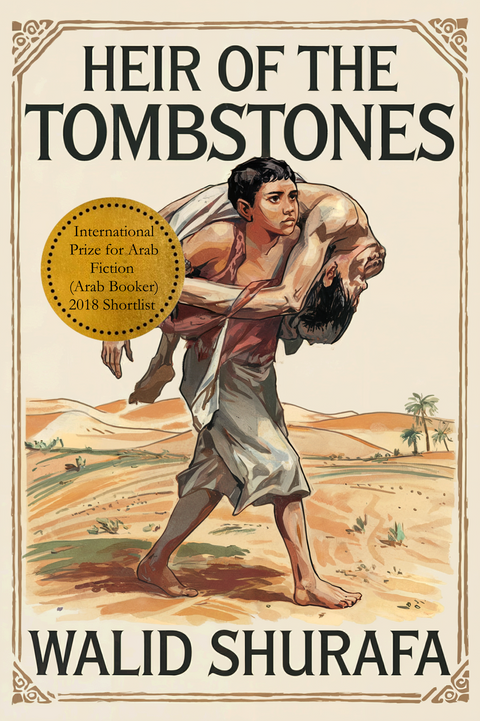

Heir of the Tombstones

Read e-books on your Kindle or your preferred e-reader - click HERE to learn how!

Walid Shurafa is an acclaimed Palestinian novelist and playwright. His novels often explore social, political, and existential themes, reflecting the complex realities of the Arab world.

Heir of the Tombstones, short-listed for the prestigious Arab Booker in 2018, delves into the plight of the Palestinian people through the lens of Al-Waheed, who recollects his childhood and how his father and grandfather were forcibly evicted from their village 'Ein Houd' by Israelis. Al-Waheed's journey to reclaim his heritage leads him to a confrontation with the past and a fight for identity.

The Prophet of God, Solomon, or the King of God, Solomon — and this is part of the curse of narratives that will afflict the reader, leaving no escape — asked an afreet (a powerful jinn) about speech. The afreet answered, "The wind scatters it, and it does not remain."

Solomon then asked, "What binds it?"

The afreet replied, "Writing."

The miracle happens simply through reading, from Mount Carmel, the mountain of miracles since the days of the god Baal. It is also the refuge of the oppressed and the brokenhearted. The reader will be able to accomplish the miracle, as the wind will bind the imaginations, sufferings, wounds, and fractures of a Palestinian.

His name is Al-Waheed (The Only One) —a nickname and a fitting title. He now sits in Al-Damoun Prison, not far from his original village, Ein Houd, which, in another narrative, became Ein Hod after its occupation in 1948 by Jewish immigrants from across the world. The former Palestinian citizens responded to the Lord’s call after three thousand years to kill their neighbors.

This narrative will lead Al-Waheed into wandering and reproach, perhaps against all divine narratives.

Al-Waheed is a Palestinian historian, or one who works with history. His grandfather was displaced from Ein Houd, and Al-Waheed was raised on stories of its beauty, the sea, Mount Carmel, its birds, and valleys. He was raised believing that in Ein Houd, the sea was the house's floor and threshold, the wind its roof, and nothing tasted right outside Ein Houd.

His grandfather left the house behind along with the pigeons’ nests, forced to flee. Yet he continued to return to it in his memories, eventually building a home in Nablus as an exact replica.

The rest of the displaced Palestinians who stayed within the Prophet's Land (which later became Israel), also did the same, creating a new Ein Houd to counter the artists who had inherited the original home of Al-Waheed's grandfather to make art.

The reader will enter Al-Waheed’s mind, follow his dreams and narratives until they become closer to him than his own jugular vein, and partake in his miracles.

How could you not? After all, Ein Houd itself is a miracle in its origins.

It is said that Abu Al-Haija, one of Saladin's commanders in the Battle of Hittin in 1187, came as a liberator of Palestine (or a conqueror, as Al-Waheed puts it) in a moment of tension between Christian and Islamic narratives.

Abu Al-Haija showed unparalleled bravery, earning Saladin’s recognition. To honor him, Saladin ordered the throwing of a drum, which flew from Hittin between Tiberias and Nazareth, landing on a rock so firmly that its shadow was etched into the stone. Some swore they saw the drum’s imprint on the rock. Saladin declared, "This land is yours and your descendants’ after you."

And it is no surprise that, even at the moment this miracle was documented, the descendants of Abu Al-Haija still reside there.

The telling of miracles itself may lead to miraculous states. Al-Waheed is a Palestinian who has paid the price of divine narratives, and through them, created his own miracle.

Perhaps he's a miracle-working prophet, remembering God's grace upon him, for the land he writes about, Palestine, is a land of miracles. It is the land that provided sustenance to Abraham through Ishmael, or Isaac according to another narrative. It is a land marked by the curse of these narratives.

It is here that Joseph escaped from the betrayal of his brothers. It is here that Christ, the Lord — or the prophet, in another narrative — rose again after being crucified and killed, or in another narrative, was never crucified at all. Before his last drop of blood could fall, a miracle occurred when he preached to the Jews, revealing himself as the Messiah. In that moment, a miracle unfolded as he leapt from Mount Qafzeh in Nazareth, escaping their clutches and their intent to kill him.

Those who saw the rock swore they could see the marks of Christ’s body and the traces of his movement etched into it. Believers claimed they could still hear the beating of his heart echoing for anyone faithful to the Lord.

It is also said that prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven from Jerusalem on his greatest miracle, not far from the Via Dolorosa. This journey, the greatest in his faith, brought him to meet the prophets and lead them in prayer under the shadow of God.

To this day, the sacred rock remains carved open, pointing towards the heavens, restoring the Lord’s glory to the mosque every night.

Because memory and imagination are scattered by the wind, as the jinn once told Prophet or King Solomon, the reader who engages with this book becomes a partner in its miracles and blessings. However, the reader does not share in its sins, nor are they burdened by the falsehoods or distortions of its narratives.

They must, however, bear the weight of Al-Waheed’s imagination and mind, filled with pain since the moment his father was killed near Nablus in 1967. That was when the Prophet’s Land (Israel) occupied the rest of Palestine. He was only a few years old then, yet he could never erase the image of his father’s body in the grave. He was buried twice, and in two graves! This haunted Al-Waheed’s mind deeply.

Thus, the wind here urges the reader to be patient with the intricate details that Al-Waheed recounts about the house in Ein Houd, and about his grandfather who returned to Ein Houd and circled his house after death. His journey was aided by a Palestinian Christian doctor who was overcome with doubt and guilt over the entire narrative!

And the messenger of the wind does not fail to point out that the reader bears no sin for Al-Waheed’s dreams, nor for the whims of the Christian doctor (at least for now) nor even for the idle chatter of Rebecca, Al-Waheed’s unconverted wife, or of his young daughter, the little painter Layla.

Thus, every reader who engages with this "pact of the jinn" will, through their reading, breathe new life into Al-Waheed and his one and only narrative, which, despite its miraculous nature, can still be seen with the naked eye and heard.

And since honesty requires returning trust to its rightful owners, the covenant of writing here calls upon the reader not to be alarmed, nor to believe the slander that Al-Waheed has become a murderer, bloodthirsty, or even ungrateful. These are traits that cannot coexist in a prophet who is both truthful and loyal, except, perhaps, in certain narratives of the Israelites in their books, scrolls, and tales of jinn.

The writer now advises the reader, who trusts in this story, not to despair or lose hope, but rather to be patient with the pains that befell the righteous Suleiman, so as not to stray or lose his faith after his steadfastness, and to avoid becoming like an old, withered palm stalk. For everything has been accomplished, and the patience you endure is not lost in the eyes of the Lord.

Since revealing the unseen is the simplest form of miracles and grace, the doctor will engage in an action he once despised and belittled, something he never believed in: writing, a task pursued only by the infatuated, the sick, and those driven by desires.

The doctor will take the covenant of visible narratives from Al-Waheed’s biography and his patience with him, and how God guided them to their Palestinian identity outside Palestine. And how he deviated from the question of love to the question of justice through his journey with Al-Waheed and his experience with his stories.

For when Al-Waheed saw his home in Ein Houd, soaked with urine and feces, and the filth beneath the feet of the dirty travelers, and after the new artists moved the plaque of his home from above the door to the lower floor of the bathroom, he took up the stone as an arm.

The doctor will serve as the interpreter for the tongue of the jinn and will attempt to translate the language in which Al-Waheed's wife wrote about her interpretations of his prophecy (which aren’t unified) into clear Arabic, the language of the Palestinians in most narratives.

He will read to the children of Israel and others, on the glorious day that he publishes her sorrow, her truth, and her refusal to accept Al-Waheed as a cruel murderer, declaring that she is among those guided to his message, announcing the birth of a final religion—the religion of Al-Waheed—and announcing that her idea of humanity was a lie.

Perhaps, though it is not certain, the doctor may interpret differently the message of Layla, Al-Waheed’s only daughter, who painted her two homes without having seen them: her grandfather's house in Ein Houd, and her grandfather and father's replica house in Nablus.

In concluding this introduction between the miraculous and the earthly, every reading in the name of Al-Waheed will revive him, along with his pain and memories in the face of evil incarnate.

Perhaps—and God is all-knowing— this will help realize his vision and what he will say in the court preceding the conclusion of this strange incident: that he knows the unseen and what is hidden, that bullets cannot kill him, that fire becomes peace and coolness for him, and that his blood, like seawater and wind breeze, cannot run dry.

The times of these stories are profound, as deep as the stories themselves, and their places are vast and extended, passing through locations like Haifa, Acre, Nablus, Beirut, Jerusalem, the desert, the new western lands, and the refugee camps.

Therefore, the reader should be at ease with the safety of their soul, because their participation in the miraculous does not imply participation in the sins mentioned within.

The end of the story approaches me—the story I've heard for more than forty years now draws near my neck, bringing an end to the wavering between tales. No one who witnessed the first story remains, except for one woman, my mother. But she will end the story as we began it together: me, her, and my grandfather.

This is the final chapter.

About fifty years ago, I was the fourth child living with my mother and grandfather, playing, having fun, and waiting for news of my father's return home.

The sun set that day. My grandfather took my mother to our house and then went to the big house. I slept in my mother's arms while she kept looking out the window, stroking my hair. Her face was red, very red, and her eyes were wet.

In the morning, I stand between them again, looking, waiting, returning.

A storyteller who came from the city said: "The Jewish soldiers killed someone at the camp while setting up checkpoints."

One of those soldiers now guards me as I head toward prison or death. The hot air and sweat clinging to my body bring me closer to the stories I heard and later recreated.

The next morning, I woke terrified from my bed beneath our house's window overlooking the valley in Umm Al-Basateen. My mother screamed a throat-tearing cry and rushed toward the valley. My grandfather followed, trying to pursue her. She fell and got up repeatedly until he caught up with her at the valley's end. He placed his cloak over her and took her inside.

I can see my grandfather's eyes now: black, sharp, staring without movement. His teeth grind against each other, and I cry at that moment, afraid for them both. I was afraid of my mother's fear, and afraid of my grandfather's unfamiliar appearance.

One of the villagers said: "Two days ago, the soldiers who occupied Nablus stopped someone returning from school, detained him, and killed him."

A passerby from a neighboring village recounted that the soldiers had stopped the man in front of their armored vehicle and ordered him to raise his hands after taking his books. When he raised his hands, one of the soldiers aimed from afar and shot two bullets into his chest. He fell and began bleeding.

The soldiers waited until evening and asked two detainees to dig a grave beside the main road leading to the city, between the city entrance and the army camp entrance, exactly three meters away. The soldiers ordered them to bury him before taking them back to the camp, on the next day of the Six-Day War.

This was the moment I first heard the story of my father's death. I later felt that my mother and grandfather were among the wicked, for they had passed on this tale. I was certain of that feeling, once I realized that he was the Unknown Martyr (the name given to his grave) after the sixth day of the war, when people began moving toward the city.

This unknown grave, this Unknown Martyr, would eventually be confirmed as my father. A week later, after waiting for news and stories, my grandfather would learn that this person—tall, thin, in his twenties—was the teacher returning from his school, and that he was wearing a white shirt, blue pants, and holding two history books for the sixth grade.

The people in the neighboring village would say this teacher was the son of Suleiman Al-Saleh (or Suleiman the Righteous), the migrant from Haifa, from Ein Houd village, who came to Umm Al-Basateen and built a house resembling his home in Ein Houd.

From that moment on, I would become the only son of the Unknown Martyr.

When my grandfather brought my mother home that day, he said, "Perhaps it's for the best, perhaps it's for the best."

She replied, stumbling, "But he hasn't returned for two days. I told him not to go out, the situation is dangerous. He didn't listen and left, and still hasn't returned."

My mother approached and pulled me close anxiously. I asked her then, "Where's my father?"

She said, as she went to get water to wash my face, "He'll return. God willing, he'll return."

My father never returned.

This is what my elderly mother would tell me nearly fifty years later: "Let it be, my son. What's dead is dead. And stay by my side to bury me."

I told her: "It’s Just a day or two more, mother. And I will return."

She held me and said, "What's dead is dead, and may God have mercy on him."

***

For more than forty years, I've lived between the memory of two graves and the stories of two homes. Layla will be alone now, in my house which is separated from me by a sea and an ocean, sleeping on her white bed, believing she's waiting for her father who went to check on her grandmother's health—the grandmother she never saw.

Layla will remain alone, and perhaps she'll hear the news of her father's execution for being a murderer. And I won't return to Rebecca, the only woman who insisted on loving me, and the only woman I ever touched in my life. This family will perhaps read about my betrayal and execution.

***

On the first Eid of the year of the Naksa, my grandfather would carry me, and bring my mother to the main road connecting Umm Al-Basateen to Nablus's eastern entrance. There, we would descend beside the road, and my grandfather's eyes would be filled with sorrow once again. My mother would fall, and I would run away in fear, watching as he wrapped his head with his keffiyeh. I would read Al-Fatiha (the first chapter of the Quran) for the soul of my father, the Unknown Martyr. From the windows of cars, I would see looks of bewilderment, astonishment, and pity.

I remember it now: My mother approached the grave marker, gently wiping the dirt. My grandfather read Al-Fatiha, and we returned home. My mother withdrew, crying. My grandfather took me with him. I rode behind him on the horse. He was holding on tightly, afraid I might fall.

The horse took us to the distant field where he had started planting olive trees. I hugged my grandfather as I sat behind him. The horse moved, and I clung to him even more. My cheek touched his back. I fell asleep, breathing in his sweat.

The horse stopped. I woke up.

My grandfather carried me and sat me under a large olive tree. We sat in silence, the sunset slowly approaching. He turned his back toward the west and squatted on the edge of an elevated orchard. I walked toward him, getting closer, and stood directly behind him.

I heard his sobbing. He was looking westward. He embraced me tightly.

I still remember the smell of his sweat lingering in my nose as he whispered, “May God have mercy on your father.”

After more than forty years, I would regret that I stayed asleep that day and did not wake up to bid him farewell. Only some murmurs and touches would remain to remind me of my father, who I grew up calling habibi (my dear).

I grew up hearing from my grandfather about his birth night in Ein Houd in Haifa, about what my grandfather was like—his back, his horse, his sweat—and stories about Ein Houd, about the details of the stairs and stone walls, the town cemetery, Mount Carmel, and Istiklal Street (Independence Street).

I didn’t just live between two graves, but between two towns, as it is now!

When I grew a little older, I would imagine my father's body under the earth, and I'd know that I became and remained the son of the Unknown Martyr, even though he became known. I'd continue to visit two graves when my grandfather decided after about two years to move my father's body to a new grave next to our house in Umm Al-Basateen. I'd see my mother embrace me tightly while I cried for my father whose hand I'd never hold again, and she'd say: "Your father is now among us."

Gradually I grew up, living on my grandfather Suleiman's stories. He woke early. I rode behind him on the horse and walked towards the hills of Al-Basateen, which extended laterally like a great staircase of orchards. My grandfather planted it with olives and grapes, and always kept looking at our house. He would tell me about the carob trees he planted to always remember the smell of Ein Houd in the morning.

When he prepared breakfast for us, he would say: "I was at a moment like this, facing the garden, near the sea, at the valley where water flows toward the sea." He would drift off and look westward, describing the morning dew and the light fog that made the prickly pears soft.

He would say: "Your father was born before the occupation of Ein Houd. I used to place him under the carob tree, the one whose stone wall collapsed later, exposing its roots lengthwise. This tree lies at the southern corner of our house, which sits at the center of the village, facing the sea. My father planted this tree when we first started building the stone house."

He would describe the house while sitting and looking west: "The house is surrounded by a stone wall that your great-grandfather built, stone by stone. The door is an arch, and from there you enter a stone courtyard, walk toward the large house, the storeroom, and the guest room. To the west of the house, toward the sea, there is a stone staircase that leads to the roof, where you can see the sea mist and its blue color through a dense, intertwined green forest. You will smell it even more."

He would continue to describe the house, the carob tree, and the four cypress trees that my great-grandfather, Saleh, planted in 1935, parallel to the stone staircase. Here, my grandfather would stop at the step where he used to sit and drink his morning tea on the second step:

"When I grew older, around twelve years old, I remember witnessing the day your great-grandfather Saleh slaughtered three goats and invited the people of Ein Houd to a feast in the only mosque that stands at the heart of the village. The mosque’s courtyard became a prayer space for the grandfather and the house. I would carry the cooking pots, the food, and the meat, and I would be exhausted as I carry the water pitcher for the people to wash their hands.”

I would hear those stories as if I were a bystander. As I grew older, my grandfather grew older too. I would go to school, and the trees would cover the hills of Al-Basateen. The carob trees would grow, and my grandfather would continue to retell the story on the way back home from one of Nablus's hills spread across Mount Gerizim.

The elevated house, which my grandfather designed similarly to the Ein Houd house, with additional rooms, overlooked the west. He would repeat to me the scene from about twenty-five years ago. "While I was in school, your father, may God have mercy on him, rode behind me."

I would stand listening, perched behind my grandfather, arms wrapped around his waist and cheek pressed against his sweaty coat. I would inhale that familiar scent—his sweat mingled with dust and the horse. My head would sway with the same rhythmic motions along the winding road. The grape vines, cypress, and carob trees would grow larger, the story would grow, and I would grow too. My grandfather would raise his voice and say:

"Listen, my son, would you believe it's the same road? In Ein Houd, you could feel the earth speaking to you. I felt the carob tree (Umm Al-Shrush, as the townspeople called it) smiling at me, waiting for me as I approached.

“I sensed the stone steps—seven of them, each made of six stones covered in grass and blackened with age—waiting for me to drink tea and eat the za'atar bread your grandmother used to bake. I would look westward and see the sea reflecting the sun's rays and the evening mist among the grass."

He would tell the story again for the millionth time, about the earth thick with trees, the wild berries and apples, especially in the rain, and the smell at Bostan Valley and Falah Valley, which flowed to us from the orchard. The smell was indescribable as the river mixed the water, flowers, and earth. The sun would sink into the sea, and my grandfather would say, "It will return from the eastern side, as your great-grandfather, Saleh, would tell me."

As we approached the house, he would tether the horse and say, "Look to the east in Ein Houd. Behind you is Mount Carmel, its sharp, sloping face over the land and sea. To your left, you will see the white houses of Haifa as tiny dots, and its streets like black veins. The waves of the sea will appear as fine, fluctuating lines."

At night, my grandfather would prepare dinner, and my mother would come to wash my hands and feet. I knew she'd been at my father's grave. She would hug me and feed me white cheese with olive oil, while my grandfather would say, "He will always be my child, no matter if it's his wedding day." My mother would respond, "Let him feed himself; he's grown now."

My grandfather would talk about dinners in Ein Houd, about the sound of the birds and the flowers of Carmel, the backyard garden where he left about twenty trees of pine, carob, and oak, and the graves of his three ancestors: his grandfather Saleh, his great-grandfather Mahmoud, and his great-great-grandfather Abdul Rahim. He would describe the tombstones, specify the color of the stones, and the type of soil where they were buried.

He would return again to the scent of the dinner on the steps of Ein Houd, the sea air in his nose, the quail and colorful birds, the heavenly valley between the root of Carmel and the sand of the sea, and his morning walk from the house to Falah Valley.

From my mother, when I entered the house, I would hear a different story. She would say, “Your son has returned, teacher,” as she prepared my bed. ‘Teacher’ was the title my father had been given in Umm Al-Basateen before he became the Unknown Martyr. She would repeat this, addressing his black-and-white photograph hanging on the wall, counting the days, saying he would always be with us.

When night fell, the demons would spread, and I would remember my father's grave. My memory would endlessly replay the final scene: the streams of school students in Nablus, the wreaths, the fragments of words written and attached to the wreaths with plastic wires, mourning "the martyred teacher."

My grandfather would continue adjusting the plastic wires, the names of schools, and the wreaths. When the flowers withered and the green leaves dried, and only the wires and plastic remained, he continued to adjust them, and they would stay on the grave until they disappeared.

My grandfather would remember his father’s grave in Ein Houd, and what happened to him, along with the birds and some pigeons for which he made a tower near the carob tree, Umm Al-Shrush, and the wheat threshing area beside the wall to the right of the house entrance.

I would grow up among stories and tales. I would come to hate the tales and the stories. I would reach high school and suffer from the tales and the waiting. I would clash with students who gave me two nicknames: "the stranger" and "the son of the Unknown Martyr."

They harassed me over school results. Once, I fell to the ground as they attacked me, and I heard the words stranger, orphan, loner. The principal — who was kind — said, "Shame on you, boys. Shame on us." He listened to the stories of the five boys from the camp.

The first said, "We were just walking when he started it." The second said, "He called us stupid." The fourth continued, "He insulted my father." The third added, "He started the fight." The fifth concluded, "For months, we’ve been enduring his behavior because he’s alone and an orphan."

I refused to argue or respond, and the principal told me, "You’re alone, my son, take care." He would listen to the students' testimonies against me, but he didn’t punish me, only saying, "Take care of yourself, and may your father rest in peace."

I hated the stories in books and texts (like the story of the day the white bull was eaten), and I felt defeated and broken by the tales of the battles of Badr and Uhud. I was not amazed by Khalid ibn Al-Walid’s heroism when he circled Mount Uhud.

I would sympathize with Prophet Joseph and Prophet Noah, and I would cry in elementary school over the dog that the homeowner killed when she thought it had attacked her infant, only to find out it had killed the snake and saved her child’s life—all because of blood stains that she had found.

I would cry in sorrow and regret, and my throat would ache. This is how I came to hate the stories; I was always its victim, in front of the principal, and in front of the students' testimonies against me. I was the lone voice, the only one, the orphan, the stranger, and the son of the Unknown Martyr.

What made it worse was that I was the only student whose mother, and not father, came to meet him halfway down the road to the school. They made two exceptions for me: my mother was the one who came to meet me halfway, and my father wasn't present at every school event requiring parents' attendance.

I would follow my grandfather after school hours. He would hurry to meet me in the middle of the orchards. He would be overjoyed that I’d grown and started carrying water and provisions for him, as well as hay for the horse. He would carry it for me, and we would have lunch together.

This old man never tired. He would tell me about the taste of tomatoes, mulberries, carob, and wild apples in Ain Hud, and his eyes would wander with every bite he took. He would tell me about his last day in Ain Hud with my father as a child. He would repeat it every day without making a mistake or slipping a word.

Every day, he would smell the bread and yearn for its taste, along with the scent of smoke mixed with cypress, pine, and rosemary.

My grandfather would carry the horse's feed and recount the last day in Ein Houd before the settlers from nearby Atlit attacked us—settlers who had been neighbors before that day.

He would describe the smoke and gunfire: "They attacked us at night, slaughtered the livestock at the town's borders, and started approaching. They demolished the house over the head of the midwife Saadiya, the only widow. They carried her from the rubble.”

He would describe how the fleeing people saw her fragile body curved against the stone wall in front of her house, blood covering her head, her fingers crushed and mixed like torn flesh. She was bent over the wall from her back.

Now, here in this dark cell, I interpret it as an earthly crucifixion—her head had drooped toward her demolished house while her stomach rose and her legs dangled toward the road.

Through April precisely, my grandfather would count the days and tally the trees burned from April to July of 1948. He would describe the settlers with their cannons and iron helmets, and the nights spent hiding in the Carmel caves, which had transformed from childhood playgrounds into shelters from settler artillery.

He would ruminate over the burned trees and two young men who were martyred, their portraits hanging on his gate. He would weep when the mosque was occupied, as despair and fear for my father gripped his heart.

His eyes would well up with tears as he recalled his final glance before locking the house, after cramming the pigeons into the guest room. He placed the grinder under the bed and carried my father alone on his back, having sent my grandmother to Nablus to stay with his friend who worked in the grain trade.

***

I look out from my damp cell corner in Al-Damoun Prison—built on the neighboring village of Daliah Al-Carmel—feeling like a pile of bones every time I wake up.

The details of my grandfather’s visits to Daliah, separated by walls that had been designed to contain the smoke since the days of the British mandate, echo in my ears. I will store these memories between consciousness and delirium, between helplessness and the ability to wake up, after I have turned into a monstrous killer, to delay the last story that will never be written.

- Literature

- Society & culture

- War

- Drama