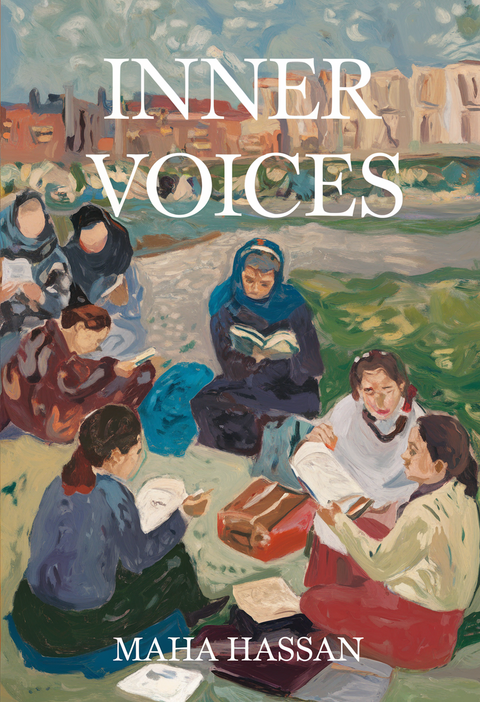

Inner Voices

Read e-books on your Kindle or your preferred e-reader - click HERE to learn how!

Maha Hassan, a celebrated Syrian-Kurdish novelist and journalist, has earned critical acclaim for her powerful storytelling, with her works shortlisted for prestigious honors such as the Arab Booker and the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature. In 2000, her daring and evocative prose led to a publishing ban in Syria, branding her writing as 'morally condemnable.' Since 2004, she has been living in exile in Paris.

Inner Voices is a metafictional novel told through two intertwining stories: the first is the inner monologue of an author writing a novel; the second is the story of the characters she is creating. As both narratives unfold, imagination and reality merge, showing how writing can both liberate and reveal.

To Philippe Adouard, the man with whom my narratives lived and thrived, free from the anxieties of existence.

To the women storytellers across the world whom life did not help publish their novels publicly, and so they lived and died in darkness.

I live two lives: one is the everyday life of routine and necessities, and the other is the life of writing, which sometimes remains unrealized. It’s as if I were a typewriter or keyboard, transcribing an entire internal world—a rich, dense life equal to dozens of visible, external lives.

"I lived to tell stories," says Márquez, expressing the intensity of a novelist's life.

"I was created to tell stories," I say, as I live inside my novel. I take my characters with me wherever I go, spying on the world to capture and transform it into accessories in my writing—people, places, smells, colors, and foods.

In this way, I imitate my grandfather, whom they called Abu Al-Qaraqie because he collected everything he came across, insisting that it "might come in handy." A qarqoua means a worthless thing, in the popular sense, but my grandfather believed everything could have its important place.

My grandfather's magical bags were filled with contradictory items: a nail, a piece of wood, spare parts for washing machines, refrigerators, or watches. He was obsessed with having replacement parts for when anything broke at home.

My father, in his way, inherited this obsession with fixing things, though he never dared collect discarded items from the street. Instead, he dismantled broken items to salvage parts he thought might be useful for future home repairs he volunteered to do.

I am heir to both of them, obsessed with dismantling the world and rebuilding it. I snatch my stories from around me.

At the laboratory, waiting my turn, I contemplate faces:

"This one won't work as a fictional character." I mentally discard them.

"This old woman resembles Shahnaz's grandmother in my current novel; I'll capture her spirit."

Thus, I record details of those who will be useful to me.

I steal their spirits without their knowledge, make small copies of them, and hide them in my little mine. I collect them from the street, metro, café, Facebook, parties, celebrations, and grand occasions. I take pieces of them—an eye from here, a look from there, a touch from here, a smile from there.

I put them in my mine, melt them in my imagination, and they emerge as new beings unlike the originals, because the fingers of writing intervene in modifying details and features, like my father's screwdriver that takes a screw from one piece to put in another.

I steal this world just as Jean-Baptiste Grenouille stole the scents of women's bodies to make his perfume. I kill the external world to recreate it artistically in a world destined for greater immortality, where Madame Bovary became more important than Flaubert, Antoine Roquentin more important than Sartre, Raskolnikov more important than Dostoevsky, and other heroes whose importance lies in not being made of flesh, blood, and divine creation, but rather heroes on paper.

Created by human imagination, they were given the possibility to exist in multiple forms in the reader's mind, and perhaps on cinema screens, to live multiple lives, not just one life confined between the dates of birth and death.

They live in the novel, that mine birthing multiple lives. The mine contains multiple layers of people, stories, and places living within it. Unlike the enormous layers of accumulated real lives which end in death, the novelist's heroes' lives endure.

One life is not enough for the novelist.

Many mining projects that workers labor on for years and years lead to no tangible results except endless digging and sculpting. Some die, leaving behind works we never hear of. The novelist’s life is similar: years of writing, sometimes dying before completing their project, taking their characters and stories with them.

Do they take them to amuse themselves there? Do they continue writing, or do they all evaporate—novels and novelists alike?

If only a novelist had ever returned from there to tell us what became of their characters and stories.

But no one returns from there.

Every night, before I drift off to sleep, as soon as I turn off the light, the story begins. Each night brings a different narrator, male or female, and a different tale.

Sometimes I'm tempted to turn on the light to discover who the narrator is, but then I remember that eternal warning stuck in my memory—about the story of the girl who was loved by a mysterious being. He implored her never to turn on the light when he visited, if she wished their love to continue.

One night, the girl couldn't resist her desire to see her lover's face, who had told her he had a camel's head. According to my treacherous memory, which tells me a different version of the lover's true nature each time, the girl who lit a candle gasped when she saw the most beautiful face in the world. A drop of melted wax fell on the lover's face, and when he awoke, he vanished forever. The girl, deprived of her beloved, suffered regret, sadness, and separation until she died of grief.

This story keeps me from turning on the light to see the face of the narrator, who is different every night. Sometimes I become so absorbed in the beauty of the story that I forget this thought and fall asleep, right in the heart of the tale.

In the morning when I wake, I hear another story—either a new one or scenes and fragments from previous tales—without seeing the narrator. As I walk, I feel possessed by my stories, filled with characters and many events I've never experienced, read about, or even seen in cinema or television. I'm like a vessel storing tales, or an old barrel in a warehouse, like a wine or oil barrel, filled with stories and sealed tight so they won't spoil, fly away, be stolen, or escape somehow.

I am this barrel, this vessel, this warehouse. However I move, I hear voices from within, and I see myself like a screen endlessly showing films, even during sleep. Colors, smells, streets, neon signs, shop names, cafes, gardens – this entire world unfolds inside me, parallel to and intensified from the external world of cities and geography.

Every morning, I discover a new serving, recalling what I experienced at night, unsure if they were dreams. No, they weren't. They're real things, or they'll become real when I put them on paper. They're places, deserts, mountains, and people. They emerge from memory or come from afar. Sometimes, they emerge from history. They regain the lives they lost and live on in the story.

That's how they live forever—good people and bad, men and women. Especially women. I hear their stories and wish I could see them. We become friends, rejoice, cry, and play together. We experience a freedom we are denied in real life. We live without secrets. We reveal our lives, our passions, our desires, our past… everything we used to be ashamed of.

For we tell the story about others, even if we are its heroes, even if we narrate it in first person. It's still a story, and we can hide behind it to say what we dare not say otherwise.

Morning stories have a different, fresh taste. How sweet it is to write in the morning!

But I must go to work.

He didn’t notice me as I entered through the wide door and headed straight towards the timekeeper's desk to log my arrival time at work.

With a gentle, deliberate movement, I removed my spotted shawl from my neck to place it beside me, on top of my large brown handbag, where part of a book's cover peeked out.

Focused on the sign-in register, I record my arrival time to the minute: eight twenty-three. My right hand holds the signing pen while my left rests on the spotted shawl and bag, afraid it might slip, as often happens, spilling its contents.

I'm passionate about reading everywhere. The first thing I do before leaving in the morning is stuff my book in my purse. I pull it out to read when I enter somewhere, or stop reading because I'm heading somewhere else. I rarely close my bag, forgetting it open, and often make sudden movements that cause its contents to spill.

"Seven minutes until I close the book," said the timekeeper.

I looked at my wristwatch and replied, "But seven minutes is still time. In one minute, the face of the world can change."

I hadn't expected anyone could read the book's title on its spine, visible from inside the open bag, unless they had keen eyesight and knew the book well. From this moment, from my hand moving the spotted shawl (snakeskin), and my hand absent-mindedly caressing the novel's cover in my bag—from this moment, the events of this novel would begin.

In the elevator, I gently pulled my spotted shawl and tucked it inside the open bag.

He was watching the elevator buttons. After approximately half an hour, he took the elevator down to the warehouse, where it had stopped for me earlier, and where I worked.

I was busy unpacking new hose boxes that had arrived at the warehouse last night at the end of the shift, which I hadn't been able to organize. As I climbed up and down the metal ladder, organizing the hoses on the third shelf, I heard his footsteps.

He stood before me with his cigarette. I looked at him from atop the ladder and felt sudden dizziness.

"Smoking isn't allowed here. Can't you read?" I pointed to a sign that read: No Smoking, Flammable Materials.

He threw his cigarette on the ground and crushed it with his shoe. I jumped off the ladder in a swift motion and picked up the cigarette butt. The ladder nearly fell on me.

"What's this mess? Don't you see the floor is clean?"

"Are we in a hospital?" he retorted sarcastically, then added, "But I didn't see any ashtray."

"I told you smoking is forbidden."

I put the cigarette butt in the trash bag in the small corner separated from my desk by a black curtain, and returned to open a new box of merchandise to arrange its contents on the third shelf.

"You work here?"

"What does it look like?" I answered briefly, surprised by his presence before me. Usually, only workers transporting goods to and from the warehouse enter this place.

"Alone?"

"Do you see anyone else?"

"Why do you answer questions with questions?"

"Why do you ask naive questions?"

"Am I bothering you?"

"I don't understand what you're doing here?"

"I saw you upstairs earlier and wanted to know about your work."

"I work in the warehouse, as you can see. Who are you? What do you want?"

"Does it matter to you?"

"You're in my workplace. I'm responsible for these items."

"Are you afraid I'll rob you?"

"No, you can't. Surveillance cameras are planted everywhere, recording every detail."

"Where can I smoke?"

"You came down here to smoke?"

"No, I came down to talk to you, but you won't stop moving up and down with these piles."

"These are hoses. It's merchandise, and it's my job."

"I don't care."

"Why do you want to talk to me?"

"I don't know."

"Do you know me?"

"I want to know you."

"You're strange."

"And so are you."

"Do you think we're in an absurdist play?"

"Do you like Beckett?"

"No."

"You prefer Ernesto Sabato?"

Only here, at this phrase, did I stop moving up and down and look at him. I looked at him. For the first time, I truly looked into his eyes. And for the first time in my life, I felt flustered before a man's gaze.

"You saw the book?"

"It was inside your bag."

"You spotted the title? From inside the bag?"

"Your bag was open, and half the cover was sticking out."

"You know the book?"

"I love Sabato."

"What do you want?"

"To smoke."

"You insist on smoking here?"

"Yes."

"Look," I spread my arms to gesture, "the place is filled with oils, grease, and flammable materials."

"Isn't there a corner where we can smoke in peace?"

"I don't smoke at work."

"I need a cigarette."

I wiped my hands of the dust from boxes and hoses, cleaned them on my skirt, shook them off and asked him to follow me. I opened a door leading to a square space, which in turn overlooked an empty lot.

"Here, you can smoke."

Before I could leave and go inside, he grabbed my arm.

"Stay with me."

"I'm cold here."

"I won't stay alone."

"I'll get my coat."

I went to get the coat, feeling as if I were playing a theatrical role. I get this feeling sometimes. I feel like I'm doing things outside of reality, acting as if I'm asleep or absent from myself, not in control of my behavior, as if I'm borrowing my body while my mind is elsewhere. I talk to non-existent beings, hear voices chattering with me, whispering to me.

I have no time to think now, forced to act according to the situation. I'll think later about who this man might be, where he came from, and if he's real. Did he put out his cigarette on the warehouse floor? I must hurry to him now, before his cigarette ends. I don't know why "I must hurry to him"? Why do I feel this curiosity?

"Are you a customer at this company?" I asked.

"No."

"Do you work for the company?"

"No."

"What are you doing here then?"

"Circumstances brought me here. I'll explain later."

"So you don't work with cars?"

"No, I'm a lawyer."

"That's a good profession."

"Maybe."

"Don't you like it?"

"Not much. And you—do you like your job here?"

"This isn't my profession."

"How so?"

"It's work to make a living, not the work I love."

"And what work do you love?"

For the second time, I looked into his eyes. And for the second time, I felt flustered before a man's gaze. I extended my hand toward him, asking for a cigarette. This was the conversation dearest to my soul at that moment. I needed a cigarette.

He handed me one without surprise, as if he had expected everything I was doing, as if he knew me. Was this part of a pre-written script? He lit my cigarette, moving close to me. His breath collided with mine, suddenly turning my heart into a trembling bird between my ribs.

I said with confidence and strength as I exhaled smoke from my chest, "If I could choose the profession I love, I would choose writing."

"What kind of writing?"

"Novels."

"Is that why you read Sabato?"

Taking another drag from the cigarette, I moved closer to him, rested my head against the wall near him, almost touching him. As if whispering to him, I said:

“I sometimes feel as if I've stepped out of a book.”

He didn’t smile or show any signs of surprise.

"That happens sometimes."

"Does it happen to you?"

"No, but I've heard of people who experienced this."

"I've never heard or read about this."

He crushed his cigarette against the wall, silently wondering where to throw the remains. I took the cigarette butt from between his elegant fingers and tossed it into a corner.

"I'm like this cigarette butt. I feel like I’ve been tossed into a corner.”

"You just said you've stepped out of a book. The cigarette butt I threw away is insignificant."

"And what about a person stepping out of a book? Are they significant?"

"Of course."

I pressed my lips together and remained silent.

"May I invite you for coffee somewhere?"

"I don't go out with strangers."

"But I'm not a stranger."

"How so?"

"Didn't we just talk?"

"Is that enough?"

"Enough for a cup of coffee."

"I'm cold, shall we go inside?"

I walked inside, keeping my coat on. I asked myself and quickly replied, "No, it's not fiction.” Then I found myself thinking, "But time is short for me. As long as I'm inside the event, I won't be able to determine if it's reality or fiction."

"Well, shall we go?"

I stood silently, so he continued:

"Alright. Listen, let's assume you are, as you say, a fictional character who stepped out of a book. Why don't we discuss this as if we're living in a novel?"

I liked what he said and nodded questioningly.

"We'll go out together, have coffee somewhere, and chat like we are chatting now. Then you'll return here, exactly as if you've stepped out of the novel into life, or returned from life to the novel."

I couldn’t debate the idea for long in my mind. He spoke as I thought, with my same logic. What's the difference between a book and reality, between written stories and the oral ones we live? Who determines if what we're living isn't also a novel?

He's playing with my thoughts, as I try to live as if I'm in a novel.

"Do you have money?"

"Plenty."

"Good, I don't have any. I'll go with you, provided you bring me back here."

"Agreed."

"Go ahead, I'll call the warehouse supervisor for permission."

Then I added, "We only have one hour."

"Fine, a novelistic hour is enough."

I laughed, "A novelistic life for one hour."

- Literature