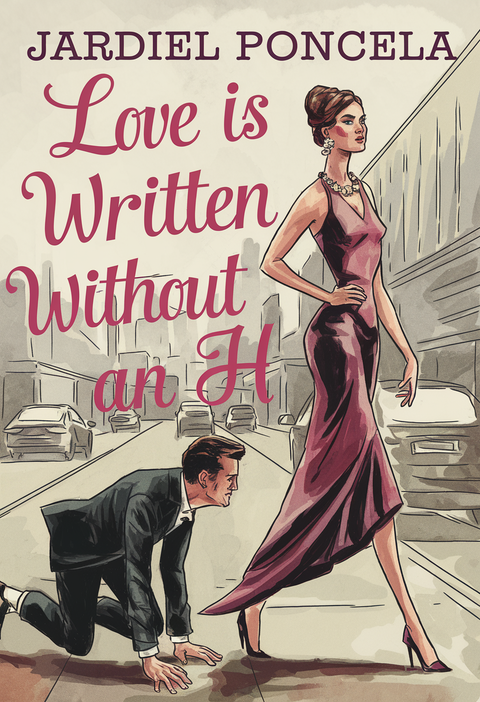

Love Is Written Without An H

Read e-books on your Kindle or your preferred e-reader - click HERE to learn how!

Enrique Jardiel Poncela, a Spanish novelist, playwright, and humorist, revolutionized 20th-century Spanish comedy, with his signature absurdism, coined as 'Jardielismo', influencing a multitude of authors. Many of his works became bestsellers, with several of his works adapted for film. Poncela also had a brief stint in Hollywood working as a screenwriter with Fox.

Love is Written Without an H is a satirical novel that parodies romantic literature of the 1920s. Through a series of humorous and absurd adventures, the book critiques the conventions of love and relationships, ultimately suggesting that love, devoid of its idealized notions, is not worth the suffering

Reader, dear reader, some authors beg you not to lend their books to anyone, because by lending them, you put your friends in a position where they need not buy them, thus harming the writer's interests.

I, who share the same interests as other authors, ask you for quite the opposite: to lend this book as soon as you read it. Since the person you lend it to won't return it, you'll hurry to buy another copy immediately. You should also lend that second copy and acquire a third one and lend it; and get another one and lend that too...

With this system, with just a few friends to whom you regularly lend books, I'll do good business and be most grateful to you.

EXPLANATION – BRIEF BIOGRAPHY – FROM BIRTH TO TODAY – PHYSICAL PORTRAIT – MORAL PORTRAIT – OPINIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS – LOVE AND WOMEN – MY DAUGHTER EVANGELINA – HUMOR – WHY THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN

"Talking about oneself is always fun."

-Heine

After writing, in ten years of literary life, over a thousand articles and stories, twenty-six novellas, sixty-eight comedies, and countless other unclassifiable works, I offer you, readers, my first full-length novel.

Allow me in its prologue to tell you about myself, my life, and my ideas. Today, everyone talks about themselves - even funeral coach drivers. Besides, I'm quite confident this book will entertain you, and since I've countless times finished reading an entertaining book and regretted not knowing biographical details about its author, wondering intrigued: "What might they be like? Are they single or married? Do they prefer their meat roasted or fried?" etc., etc., I'm doing what I can so this doesn't happen to you.

Perhaps what I tell about my life isn't too interesting, but Wilfredo the Hairy's life is even less interesting, and it's printed across all five parts of the world. Speaking about oneself is as dangerous as it is pleasant. There's a risk of falling into stupid vanity, and there's a risk of shipwrecking against the rocks of false modesty.

For my part, I've tried to avoid both risks through extreme sincerity. I know in advance that the prologue will turn out very passionate, and I don't mind. That is to say: I prefer it that way. The serenity of judgment, something I'll unfortunately end up possessing, I gladly gift today to the disciples of that literary refrigerator called Don Juan Valera.

Perhaps the prologue will also turn out a bit cynical. It's inevitable. I'm going to tell truths, and truth is only separated from cynicism by a modern house partition.

I certainly could have entrusted a highly prestigious writer with the task of giving you details about my existence and ideas, and thus their flag would cover my merchandise; but that widespread procedure seems as foolish to me as entrusting a silver-tongued friend with the mission of declaring our love to the woman we desire.

Brief Biography

Here might fit well 21 "alexandrines" that I scribbled some time ago in the album of one of those young ladies who collect writers' autographs, without realizing that collecting current account holders' autographs from the Bank of Spain would be more useful.

The verses, which are a brief biography, were titled:

Portrait in Pastel (from puff pastry)

And they said:

I was born creating the commotion typical of such scenes;

baptized by the Church according to its rites,

and Aragón and Castile flow through my veins,

transformed into the red calcium of my erythrocytes.

Which of the two regions weighs heavier on my heart?

It’s hard to uncover the key to this mystery...

Perhaps Castile weighs more when I grow serious,

and Aragón, perhaps, when I am joyful.

Like many other creatures of diverse origins,

I was raised in the fear of the God of the Heights;

but I lost that fear—or faith, which is the same—

years later, when I took up mountaineering.

I write, for I have never found a better remedy

than writing to chase away tedium,

and in the sharp crises that punctuate my life,

I have always wielded my pen as an insecticide.

Outside of these pages, I know no other “nirvana.”

Glory means nothing to me, that vile courtesan

who kisses everyone alike: Lindbergh, Chaplin, Beethoven...

And I have never saved for tomorrow,

for I am convinced that I will die young.

But let us leave behind the rhymed form…

From Birth to Today

I was born to my parents' satisfaction, who, after three consecutive girls, wanted a boy—two of whom survived—on the morning of October 15, 1901, in Madrid, on Arco de Santa María Street (now Augusto Figueroa). Therefore, I am twenty-seven years old at the time this book is published.

My childhood unfolded in an environment steeped in art and intellectualism, and by virtue of living with such influences, I've learned not to give them much importance. (In this regard, I differ from many other writers, the "nouveau riche" of art and intellectualism, who are not accustomed to these things and inflate with self-importance like tyres when suddenly immersed in such concepts.)

I grew, the little I have grown, surrounded by books, magazines, newspapers, paintings, and sculptures; I saw printing presses operate before I saw can openers, mastered Mythology before Sacred History, and understood socialism before football.

The bluish shadow of my mother, who passed away eleven years ago, hovered over my childhood, instilling in me good taste, delicacy, and melancholy. At four, in school, Luis de Zulueta would pick me up in his arms to teach me pieces of the Moorish Romancero, which he pronounced with a charming accent from Las Ramblas. (This is why I always thought Mohammed was pronounced Mahomá.) At seven, holding my mother's hand, I walked through the Prado Museum and could tell at a glance Rubens from Teniers and El Greco from Ribera.

(This served me well in avoiding pedantic discussions about painting now and helped me remain indifferent to various masters.)

Just as at seven years old I wandered through the Prado Museum holding my mother's tender and poetic hand, at nine I attended sessions of Congress from the Press gallery, where my father's vigorous hand filled page after page at one of the front-row desks.

(Witnessing those sessions then has kept me from returning to Congress, made me distrust brilliant men, and disbelieve in the talent of orators.)

I was always a rebellious and inattentive child.

In my school life, two unconquerable hatreds stand out: mathematics and umbrellas. I could never tolerate using umbrellas; I could never accept that "the sum of angles in a triangle equals two right angles."

(Even today, I resist accepting it.)

In contrast, fighting with classmates and skipping class brought me joy.

Nevertheless, since my comprehension and retention abilities were solid, I always performed well and got good grades in all exams.

I was educated at three schools: the Free Institute of Education (from four to seven years), the French Society (from seven to eleven), and the Piarist Fathers of San Antonio Abad (from eleven to sixteen).

From the first school, I keep faint memories of several pleasant teachers: Zulueta, Ontañón, Blanco, Vaca, guided the “grandfather”.

From the second school, the memory is sweeter. There, I fell in love for the first time. She was nine years old; I was barely ten. She was the daughter of a famous Jewish banker in Madrid, but I solemnly swear that "I wasn't after the money." At ten years old, one despises money and Geodesy. Currently, I’ve lost track of that young lady.

From the third school, I have two good memories: starting to write literature for a small newspaper we students produced, and encountering four admirable priests—Piarists Modesto Barrio, Ricardo Seisdedos, Luis López, and Luis Ubeda. The first was also an excellent sacred orator and said mass so quickly that, upon seeing him robed, we boys would breathe a sigh of relief.

From the Piarist Fathers, I moved on to the Institute and the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters. I instigated strikes, heroically harangued the "masses," set up gambling games of "baccarat" and "seven and a half," threw stones at trams, forced all coachmen passing through San Bernardo Street to salute, and was elected president of a Strike Committee that achieved the resounding success of starting Christmas vacation on October 17th.

It was an era when we students didn't study; that is, we knew how to be students. The shame is that it passed too quickly.

After that, I began journalism. Since then, I've admired those magical journalists who, in an instant, with four precise questions, learn and know everything, because my debut as a reporter was a disaster.

I worked at La Acción, a newspaper created and directed by Manuel Delgado Barreto, where no one worked except the director. One morning, Agustín Bonnat, the chief editor, called me.

"Look, Enrique," he said. "A bull killed Regino Velasco yesterday, jumping over the barrier at the Madrid Plaza while he was quietly watching the bullfight. Go to the house of mourning and 'cover' the funeral."

I went to Regino's house, the famous printer, and returned to the newspaper.

"Well?" Bonnat asked me.

"Well, the bull jumped the barrier and attacked Regino, who was watching the bullfight, killing him."

"But we already knew that before."

"Yes."

"And you don’t bring any more news? Why?"

"I thought it would be wrong to bother the family, who must be terribly upset."

They never sent me anywhere again.

I moved to La Correspondencia de España to write a daily signed section. This distinction was not forgiven by the chief editor and the political cartoonist, two very bitter gentlemen. They waged an all-out war against me and bothered me as much as they could. I carried on, trusting in my star. Indeed, as has happened with all men who have declared themselves my enemies, both died shortly after.

And La Correspondencia de España too, not to be outdone.

I abandoned journalism to dedicate myself entirely to literature. I began by writing dramatic, tragic narratives. Any subject that didn’t involve someone going through terrible trials, or that didn’t allow me to describe several deaths, suicides, or murders, was promptly rejected by me: I was obsessed with the Judicial Morgue, and catastrophes seduced me.

Later, as time passed, and when I felt pain up close, I began despising dramatic motifs until arriving at the violent humor I've been cultivating for years.

In 1922, when Buen Humor was newly founded, "Sileno," one of the most spiritual men I've known, opened the doors of his magazine wide for me. Most of my literary work is in the 400 issues published to date, and there was always such kindness, affection, and benevolence for me there that even in the brief periods when I left that publication, I never completely forgot it, and in reality, it can be said that I never entirely abandoned it.

In childhood, my first readings were tumultuous, incongruous, and diverse, as always happens to children who love books and are born to intelligent parents. Owner of several large bookstores full of volumes, I read Dante and Dickens at the same time, Aristophanes and Andersen, Pindar and Amicis, Ovid and Byron, Swedenborg and Ganivet, Lope and Dumas, Chateaubriand and Conan Doyle, and the unknown author of Cocoliche and Tragavientos.

I must declare that back then they all moved me equally, and it has taken years to understand—and to dare say it—that Tasso is unbearable and to prefer a page of Jules Verne translated by an illiterate to the entire Iliad recited by Homer himself.

I have no qualms about repeating what some might call blasphemy on Union Radio's (EAJ) microphones. These days, I read with increasing caution. I acknowledge that we are in another Golden Age of literature; there are tremendous peaks in Spain. But the current author I most enjoy remains Baltasar Gracián (1584-1658).

I live alone, weary of living in company and hoping to soon stop being alone, among paintings by my mother, furniture I made myself, and cushions gifted by my youngest sister. I earn my money honestly, through my brainwork, which is uncommon among people of the quill (writers and ostriches).

I go to bed and wake up late, as I don't believe God helps early risers; just look at chickens—despite rising at dawn, they age laying eggs for others to eat and end up dying in the cooking pot. I'll continue living this way until I start living differently.

Physical Portrait

If women suddenly stopped reading, all of us who make a living from writing would have to emigrate to Niger. What I mean is that the literary audience in Spain consists almost exclusively of women. And when women take notice of a writer's work, they rush to imagine him as they please. Then, when they meet the writer in person, disappointment follows. To prevent this in my case, I provide this physical portrait, as one can never trust photographers’ portraits.

I am ugly—singularly ugly, ugly cubed. Furthermore, I am short—one meter sixty in height, as I noted in the prologue of another book. With these first two declarations, I assume I’m already beyond the reach of passionate readers.

I am thin, with black hair, dark eyes, a sharp face, small ears, a thick beard (shaved with Gillette), and a starched collar (with ‘Brillo’). My features, which animate in conversation, have a hard expression when I'm not speaking, verging on anger. My skeleton is proportioned—twelve degrees less proportioned than "Apollo" and twenty-five degrees more proportioned than "Quasimodo."

I’m skilled at all kinds of manual work, including rolling cigarettes, though I always buy them pre-rolled from Abdulla Co. Ltd. (I like the countryside, rice, fried eggs, women, and beefsteak with potatoes.) I haven’t tasted fish in eight years; I don’t drink wine or liquor, and my organs function with the precision of a funicular. I've never suffered from repugnant diseases—those dishonorable ailments men often boast about.

My health is perfect, like Fray Luis's "Married Woman." I have resilient muscles, though it's not immediately obvious, and no physical effort has humbled them. With my right hand, I can hold 101 kilos; with my left, 56, and with both hands, I supported my household when I had one.

(I jump, run, walk, climb, and play chess without tiring. I enjoy jumping onto the back of automobiles and getting off moving trams, especially when they're "at nine.") I've traveled by foot, car, bicycle, sexcycle, train, ocean liner, airplane, locomotive, and boat. I've walked through dark tunnels and endured twenty minutes of aerial acrobatics in a military fighter plane while my safety belt came loose, forcing me to grip the seat with both hands to avoid a 2,500-meter fall. Performing somersaults in the air, with clouds below and fields, houses, and trees above, is quite entertaining.

I can consume up to nine coffees daily without my sleep being disturbed by anything other than the twelve o'clock mail. I sleep with the tranquility of the righteous and dormice, and sleep produces two curious effects: it puts me in a bad mood and makes my hair wavy.

Physically, from what I've said, I don't possess enough qualities to earn a single compliment from those versed in aesthetics. (This happens to 999 out of 1000 men, with the difference being that I acknowledge and say it, while others harbor pretensions of believing themselves handsome and seductive. Indeed, man is the animal that most resembles man.) However, perhaps due to my short stature, I exert a notable sympathetic influence over crowds, which I've verified whenever I've addressed the public in one way or another.

Moral Portrait

Regarding character, I'm an incorrigible romantic and sentimentalist. I belong, even though such a declaration might cause some surprise, to the group of

"…la vieille boutique romantique…"

Naturally, deep down, like all romantics and sentimentalists, I'm sensual, as romanticism is nothing but the alloy of sensuality with the idea of death.

But that doesn't prevent me from adoring sunsets and starry nights; from instinctively seeking sweetness in women; from enjoying kissing their hands and shoulders; from having proposed suicide to more than one after lovemaking; from certain melodies leaving me sad; from having cried without knowing why in feminine arms; and from having done—and still being willing to do—many of the simplicities inherent to romantics and sentimentalists.

Nevertheless, typically, seeing women cry makes me laugh. And seeing my daughter laugh makes me cry. I like treating humble people well and treating poorly those who find themselves at the high end of life's "toboggan." I hate the fatuous, and if laws didn't exist, I would spend Sunday afternoons assassinating with a pistol all the conceited people I know.

I would also murder those who make their voices hollow to speak.

And those who speak loudly without making their voices hollow.

In short, I would murder quite a few people.

I am cheerful, but sometimes I become very sad and have "grey days," to combat which I write verses—verses that I tear up and don't publish, because I believe that publishing and getting paid for sincere verses is as dirty as trading in the beauty of the woman who perfumes our pillow with her hair.

(These verses tend to be bad, but certainly not as bad as those published weekly in illustrated magazines.)

That is to say, I am sometimes optimistic and sometimes pessimistic, like any truly sensitive person, since life is, in essence, nothing more than a dizzying whirlwind of reactions.

I am vain.

(Everyone who creates is vain, even if what's created is an ugly child.)

I am good... somewhat good... a little good...

(Just a little, because I don't like to stand out too much among my peers.)

I am sincere, as anyone reading these pages will observe.

Nevertheless, in small things, I lie a lot; I lie without cause, I lie for the pleasure of lying.

Within my vanity, I possess great modesty, and thus compliments, while pleasing me, fill me with confusion and shame.

I have had successes and therefore opportunities for friends to organize many banquets in my honor, but I have never allowed it.

Others' opinions matter absolutely nothing to me; what others whisper about me has never made me and will never make me change my conduct.

But when I've learned that someone was slandering me, I've automatically stopped greeting them.

With this system, which I recommend, I've saved myself the trouble of talking to many idiots.

Moreover, I've never been afraid to stand against social prejudices, especially during my periods of what Pío Baroja's Larrañaga calls tristanism.

I have a soul that becomes passionate in bursts, but Destiny and waves of dispassion have never allowed my heart to fully quench its rabid thirst for tenderness.

I am variable and changeable, like clouds; what makes me happy sometimes makes me sad at others and vice versa.

I have always lived lightly, without worrying too much about problems that crossed my path, and without ever being frightened by the conflicts that my own lightness created, because I've always believed that existence is a game of chance and only disturbed people insist on governing chance with the laws of calculation and reasoning.

Nature has granted me enormous nervous resistance and a strong presence of mind to resolve those decisive moments that existence prepares for us behind the screen of circumstances.

And circumstances, for their part, have taken pleasure in offering me "decisive moments."

Opinions, Customs, and Beliefs

I have no preference for any color, as authors of the 19th century used to declare in interviews, and if forced to choose, I would choose the color "esfrucis"

The man I admire most, whom I consider the most important in the world, past and present, is Charlie Chaplin (Charlot), a true genius of all times.

I enjoy chatting, because conversation is one of the most enchanting pleasures the Greeks left us; but I try to chat little with great artists to avoid becoming dull.

Domestic animals attract me, as fashionable beaches do.

My relationship with one of my uncles, professor of Hebrew and Comparative Semitic Languages and former dean of the Central University, austere, faithful researcher, a worker as profound as he was modest, was very useful to me in learning that "Jardiel" in Hebrew means "energy" and in not ignoring that goodness, austerity, modesty, and true talent only lead to indifference and oblivion.

I detest people (writers, philosophers, or street sweepers) who denigrate the present era and present humanity to exalt other periods of History.

(All periods of History are equal, even though they're different. Modern man is as beastly and perverse as the one who heard Pi y Margall growl in Parliament or the one who drew mammoths in the Altamira cave. And as for our football-playing youth, they are neither more nor less stupid than the youth who danced at La Bombilla wearing bowler hats or those who played morra in Roman amphitheaters.)

Regarding life, I find that, like the Mississippi, it is too long. Too long, because it's enough to look back to summarize five, six, ten years in a single moment of pleasure or pain; everything else has vanished, disappeared, doesn't exist, or—which is the same—never needed to exist.

And it is also too sad; so sad that everything pleasant in life tends to make one forget that one is living.

Politically, I think that peoples only deserve an energetic "mastigophorus," and the more energetic, the better.

Traveling seduces me. The mere presence of a train fills me with impatience to go somewhere.

(Sometimes, I also burn myself with my cigar.)

I rarely go to the theater, as I'm interested in maintaining the perfect balance of my nerves, and that balance is disturbed by the sight of the foolish nonsense that is performed.

However, I go quite often to the "cinema" because, since we've already agreed it's an inferior spectacle, the good things I see in it seem superior to me.

In work I am constant, like "Macías, the enamored one." The sun rarely sets without my having written something. I write at noon and, sometimes, also in the afternoon, and sometimes, also at night. I abhor dirty jokes, those scatological jokes so pleasing to almost everyone, and before using that device to amuse the public, I would sell my pen at the Rastro.

I always work in cafés, as I need noise around me to work, and in that noise I isolate myself, like a fish in a fishbowl. I write with extreme ease, which does not exclude the yearning to improve. For example, I wrote the three acts of Una noche de primavera sin sueño (A Sleepless Spring Night) in five days, being, as it is, one of the most significant comedies premiered in the last fifty years.

I don't believe in the complete goodness of humans nor in the complete goodness of Pink Pills. (Men are such despicable creatures that it was very difficult to create another creature as despicable as us, which is why the Supreme Maker, being the Supreme Maker, took no less than seven days to create woman.)

Regarding the great problems of the "beyond," I now have ideas that bear no resemblance to those I had at first. In adolescence and early youth, I was deeply spiritual. I even wrote a book (a terrible one): "The Astral Plane," but today spiritualism draws hour-long yawns from me.

Back then, the sight of a corpse would plunge me into deep meditations. I would ask questions, imagine answers, and even believed I could see, in the clouded glass of those pupils, mysterious reflections of inaccessible regions. Today I look at a corpse and can only think to say: "It's dead."

In the evenings, from eight to eight-thirty, I "stroll" through Madrid's central streets to convince myself that the Puerta del Sol hasn't moved from its place and to continue believing that women's legs are magnificent. I enjoy stopping at the gatherings of street dentists and peddlers. I lunch and dine in restaurants, and with time, thanks to this method, I'll join the ranks of the hyperchlorhydrics.

I don't understand a word—or a note—of music. Therefore, I like cheesy melodies, trite hymns, and cheap paso dobles. (The reader will quickly understand that I'm drawn to Alonso's music.) By mistake, while dressing, I hum a dance tune from "Faust," learned from an unforgettable music box.

Of Philosophy, I think it is the Recreational Physics of the soul. And what happened to that fatal fool Stendhal with Kant's system has happened to me with Hegel, Pascal, and many others.

I won't be the one—oh no!—to stamp numerous praises of old authors here, since old authors rarely stamp praises of young authors. I will say, though, that contemporary dramatic literature is represented by the Alvarez Quintero brothers, whose work, thoroughly Spanish and saturated with wit, is superb. And I say this because in a certain interview, the Alvarez Quintero brothers declared that I wrote well. (General Society of Mutual Praise. Capital: 200,000,000 pesetas.)

Love and Women

In love, I proceed exactly like other men, barely differing from them in that I've always avoided using vulgar words. Love—what can be called love—I've had only twice. Passion—what can be called passion—I've had only once. Both times I was on the verge of marriage.

First, I loved a charming girl, but I managed to recover after seven years, and today I'm happy thinking that she surely would have made me happy. Then I loved another woman, exceptional for her dazzling beauty, vivacious intelligence, and refined spirit. She made me so happy that I was also about to marry her. Fortunately, I remembered in time that she was already married, and my wedding couldn't be arranged, which arranged everything.

This woman has been the "sun" of my solar system; the previous one was the "moon." As for the "stars," as far as I can recall:

- First, a telephone operator with whom I engaged in some casual amour au grand’air. She called me fourteen times daily at a friend’s number (22-32, Jordán). I’m not sure how it ended; I think it stopped the day my friend’s phone broke.

- Second, a slender young lady with enormous black eyes. I began a summer romance with her while explaining the meaning of the word menopause. She eventually married a young man with a Harley motorcycle and severe myopia.

- Third, a girl so strange and intriguing that she started to unsettle me. I only managed to meet her once (perhaps that’s why I found her intriguing and strange). Beyond the memory of her, I kept a garter in the shape of a pierrot.

- Fourth, another woman with a mole on her left breast, who later "THREW HERSELF INTO THE MIRE," as the zulu lyricists of Argentine tangos might write.

- Fifth, another, who fancied herself a jaded neurotic when, in truth, she was naive. She imbued our meetings with great mystery and once proposed we flee to London. When I told her I had no business in London, she got angry and never came back. Bon voyage.

- Sixth, a “chorus girl,” who was unbelievably foolish. These days, when she sees me on the street with her boyfriend, she doesn’t even say hello. And what do I care?

Some might think, after reading this, that I'm trying to appear as a "Don Juan"; nothing could be further from the truth and my intention. On the contrary, possessed by my physical insignificance, convinced that for women there is no better merit than having long legs or a big nose, it has yet to be the first time that I have approached one of them.

And it has been they, "always and in every case," who have approached me. That's why I've never feared they might deceive me with another, for what we have conquered through our own effort might slip from our hands, but what has come to our power voluntarily doesn't leave unless we detach it with energy and determination.

From all my loves I've had to detach myself, because monotony and tiredness turned my nerves into an out-of-tune xylophone. Later, when I had lost those women, I would feel attracted to them again, but by then it was too late.

Nevertheless, when encountering any of those I loved, I've always heard the same words: "I've never forgotten how happy I was with you; your way of speaking, your character, everything is different from others." (Which has made me proud, because it takes very little to be "different from others.")

Saying "I love you, my darling," or anything similar, has always been very difficult for me. I don't know what to attribute this to, because it must be noted that when I have loved, I have loved with all my soul—or in other words, I have made the chosen ones of my heart suffer mightily. (Sadism? Perhaps!)

I have no preference for blondes or brunettes. As I said before, dyes don't interest me in the least. I like women with proud expressions. (Masochism? Who knows!)

I am a fetishist, like all sensual people. About women, I have ideas that bear no resemblance to my pristine ones. In adolescence, women seemed beautiful, good, and superior to men. Today men and women seem equally miserable to me.

Years ago, it seemed monstrous to me that the Church had lived for entire centuries without recognizing the existence of the female soul. Currently, I believe the Church was right and that it recognized the existence of the soul in women too soon.

I said before that I have never approached any woman, because a woman, like a crocodile, must be hunted, and hunting is a sport that doesn't interest me; striving to win a woman seems to me a waste of time similar to feeding a calf the contents of a can of sardines in oil.

Don Juan Tenorio was, in my opinion, neither a clinical case nor a hero; he was simply a cretin without important occupations.

Any woman who aspires to be loved by me, assuming such a woman exists—which I don't doubt—must come seeking me, as previous ones did, for I am very badly accustomed to this, and then we shall see if we understand each other.

Furthermore, regarding women, I maintain a very strict criterion: either they adapt to me, my tastes, my character, and my interests, or I tie a knot in my heart and bid them farewell with melancholic firmness.

A woman who doesn't adapt to us has less value than a fruit bowl, even if she were Phryne reborn; because the "ideal woman" who illuminates our existence, simplifies it, and smooths it out, deserves everything. But the "real woman" who darkens it, complicates it, and fills it with obstacles, only deserves to be thrown down the elevator shaft. (I believe Larra gained prestige by dying from the pistol shot he fired, as killing himself over a woman's rejection showed that his privileged brain had entered a period of decline.)

Women are inferior to men in only one aspect: being obligated to personify tenderness, peace, understanding, sweetness, and patience—being duty-bound to brighten and facilitate man's life—they strive to do exactly the opposite. (And because of this, they deserve the harshest criticism.)

Man, confused and blinded by feminine beauty, has exalted woman without stopping to consider her unforgivable conduct in life.

Man has thus been the main culprit in making woman what she is and even making her worse; for by constantly praising her, considering her the axis of the World, and surrendering his brain to her calves, he has achieved the sad result that any silly girl, with nothing but pretty eyes, believes herself superior to everything around her.

I am not a misogynist. I couldn't live without women's company and presence; I like them above the salvation of my soul. What I don't do, at least for now, is give them my heart, because every time I gave it, they broke off a piece, and I need it whole for the methodical circulation of my blood.

(Women don't break our hearts because they stop loving us, as it's hard to find a being who develops the rock-solid fidelity that woman develops. They break our hearts by suddenly showing themselves to be completely different from what we believed them to be.)

My conduct regarding women is, therefore, like that of housewives who don't leave their good china in the hands of a maid who just arrived from the village, knowing she would break it. Yet they trust it without fear to an experienced servant.

I'll end this little chapter about women with two inconsequential observations:

First - I like women best when naked.

Second - Once naked, I like women best from behind.

My Daughter Evangelina

I’ve already mentioned that I have a daughter.

This daughter, whom I adore as all parents in Europe, America, and Oceania adore their children—and some in Africa, Asia, and the Polar Caps as well—is named Evangelina.

When I took her to be baptized, no one was surprised that I was single. What did surprise everyone, however, was my insistence that my daughter be named Evangelina.

“That’s not a saint’s name.”

“That doesn’t matter to me. I want her to be called that.”

“It’s not possible.”

“It has to be.”

“No.”

“Yes.”

“Then we’ll give her a different name, or she won’t be baptized at all.”

“Give her another name if you must. But to me, to her, and to everyone else, she’ll be Evangelina.”

And so, her name is Evangelina. Evangelina Jardiel Poncela.

Today, Evangelina is barely a year old. She was conceived out of love alone, which is why she is beautiful, clever, cheerful, and healthy. I longed for her long before she was born, and even before her birth, I knew she would be a girl. I had always suspected that whatever delicacy existed in my sensitivity, inherited from a woman—my mother—would pass on to another woman: my daughter.

Now, my little one spends her days devouring bottles and mashed food. Still, when I visit her in the afternoons at her nanny’s house, she stretches her arms out to me and plays tirelessly with my fountain pen. (At those moments, I wonder if she will inherit my literary affliction, and I feel tempted to take up amber pipe-making instead, to avoid passing on the same curse to any future children I might have.)

I eagerly await the day when my daughter will be old enough for me to travel the world with her, teaching her to laugh at every living creature. My greatest heartbreak, however, will be seeing her fall in love with a fool. And since Providence takes special care to make us drink the bitterest draughts we most detest, I’m haunted by the thought that this will inevitably come to pass.

Humor

I won't fall now—nor hope to ever fall—into the simplicity of defining humor, a very modern custom, because defining humor is like trying to pin down a butterfly by its wing using a telegraph pole as a pin.

Neither will I attempt to break new ground in the field of humor, because all spiritual fields are infinite and immeasurable, and all we know is that they border: death to the north, birth to the south, reasoning to the east, and passion to the west.

The admirable Wenceslao Fernández Flores said in an interview that only those born in Galicia can be humorists. At first, this terrified me, as I've said I'm from Madrid.

"My God," I moaned in anguish, "Why didn't you make me be born in Galicia? Didn't you understand with your supreme wisdom that by making me be born in Castile you were forever ruining my artistic future?"

I thought about how in reality all Spanish humorists, from Cervantes to Larra, including Quevedo and two hundred more, were ALL born in Castile and the vast majority, like me, in Madrid. Nevertheless, those were painful days.

But, fortunately, I was quickly reassured upon remembering that my wet nurse was Galician, and therefore it's probable that in transmitting the juice from her breasts, she also transmitted the necessary amount of Galician-ness to be a humorist. And since then, I've lived peacefully.

I won't define humor, no. But I will say that not everyone understands humorous literature. Which is completely natural.

Particularly, humorous literature, besides serving me for a number of things that need not be declared, serves me to measure people's intelligence, instantly and without making a single mistake.

If I hear someone say: "Well, you people come up with some tremendous nonsense!"

I think: "This one's a cretin."

If they tell me: "This kind of literature is good because it takes away sorrows."

I think: "This is an ordinary person."

When they warn me: "It's an admirable genre and I find it extremely difficult."

Then I think: "This is a discerning person."

And finally, if someone declares: "For me, humor is the father of everything, since it is the concentrated essence of everything, and because whoever creates humor 'thinks, knows, observes, and feels.'"

Then I say: "This is an intelligent person."

***

Summarizing the autobiography: I am a happy person. I'm not rich nor do I think I ever will be; but I am happy. I'm equally happy seeing how the sun floods the streets with its inimitable light as I am putting on a freshly pressed suit. The "mechanism" of my happiness is perfectly captured in the small life sketch I write below:

It's twelve noon. I leave the house. The midday heat caresses my skin. I expand my chest, breathing contentedly. Then I start walking down the street, whistling a little tune. A car passes by, I dodge it. How wonderful! I feel so agile. The trees have a bright green color. Long live the green trees! A dog sniffs at the facade of a house. I call it, I pet it; the dog wags its tail. Dogs... how friendly dogs are!

Further ahead, some children are playing. One child smiles, the other cries furiously. Ha! Kids are funny, aren't they? I continue on, feeling increasingly happy. A beautiful girl approaches. God! How beautiful she is! Her heart and mind must be empty, like all of them, of course; but how beautiful she is! What legs she has! What eyes! What a mouth! Long live beautiful women! Onward...

I arrive at a sunny, peaceful café. I spread out my papers. They serve me coffee. I take a sip. It's wonderful. It tastes like metal polish, but it's wonderful. I light a cigarette. Ah! Smoking... what a delight! My lungs must be shot to pieces, but what a delight! Well then! To work! Come on, let's see... the fountain pen! And the pages fill up, with the supreme optimism of blue ink on white, glossy paper.

Aren't there reasons to be happy?

Why This Book Was Written

You all know that erotic-novelistic literary genre that's so in vogue. During the period when I began practicing “compsilogy”—or the science of shaving oneself—I also began reading so-called "love" or "psychological" novels. I'm not ashamed to declare that I liked these novels then. I was fifteen, and I also liked drinking beer, writing letters in verse to imaginary lovers, and wearing bow ties. In such novels, I read and learned the following things:

1. That men who make women fall in love are always tall, thin, with black hair and green eyes, and they dedicate themselves to literature, painting, sculpture, aviation, or bullfighting.

2. That all of them, without exception, have a bachelor pad on Ayala Street.

3. That men who don't meet these conditions are despised and deceived by women.

4. That love affairs take place at five in the afternoon.

5. That femme fatales are found aboard ocean liners and express trains, or in London or Berlin or Switzerland or the French Riviera.

6. That when two distinguished lovers enter a bar, they always order cocktails.

7. That there are people who die of love.

8. That eternal loves exist.

9. That women of loose morals are saints, while apparently honest women are monsters of perversion.

10. That men are divided into two groups: good and bad.

11. That love is the most important thing in the world.

12. That elegant people live weary of life, are extravagant, and take cocaine, morphine, and ether.

13. That cabarets are dens of perdition.

14. That cultured and exquisite women love in an exceptional way.

15. That single young women are divided into innocent and pure, and perverted and impure.

16. That the act of making love is very poetic.

All this I read and learned in the so-called "love" or "psychological" novels. But time has passed, and life has taught me these other things:

1. That women fall in love equally with tall men as with short ones, with green-eyed men as with bulging-eyed ones, with sculptors as with business experts, as long as they have money to support them and energy to satisfy their sensuality.

2. That there aren't even five men who have bachelor pads on Ayala Street.

3. That women, when they despise or cheat, do it without knowing why, as they rarely reason.

4. That love affairs, like watchmakers, have no fixed hours.

5. That femme fatales can be found even in the “consommé.”

6. That cocktails are only ordered by four pretentious people who don't even like them.

7. That nobody dies of love, but rather of the flu.

8. That there isn't a single eternal love.

9. That all women are the same, except for differences in name, ID, and complexion.

10. That men aren't divided into groups, but into herds.

11. That love isn't as important as it's made out to be.

12. That only people who haven't digested the aforementioned love novels take drugs.

13. That in cabarets, no one becomes perverted or entertained.

14. That there isn't a woman who doesn't love in the most vulgar way.

15. That single young women aren't susceptible to any division because they form a single phalanx of "flesh-hungry" individuals, some who know what's happening to them and others who can't explain it.

16. That the act of making love has been, is, and will be a mess as lamentable as it is reassuring.

The difference between what I learned in "love novels" and what I've learned by living proves that these novels instill false and absurd ideas in young minds. I believed it necessary and praiseworthy to undo these false ideas, which can poison the clear springs of youth, and I decided to put the young people of Spain and America face to face with sincerity.

For this purpose, I have written "Love is Written Without an H," as I think that "serious" love novels can only be fought with "humorous" love novels. Cervantes did exactly the same with books of Chivalry, though this isn't to dare compare myself with Cervantes, as there are notable differences between him and me; for example: I wasn't at the Battle of Lepanto.

We must laugh at conventional "love" novels. Let's laugh. Let's release a laugh of 400 pages.

END OF PROLOGUE

Brief Appendix

There ends the prologue, as for now. I've grown tired of speaking in first person.

Everything written in it is true. However, I advise my readers not to take everything that's been said too seriously. It's worth remembering that "truth is never absolute." Everything can be true, but everything can also be untrue. And between a positive truth and a negative truth, there are countless other small truths that are neither entirely negative nor positive. It's what mathematicians—those inexact beings—call the "ultracontinuum." (This isn't new, but many people ignore it.)

IMPORTANT NOTE: The Heine quote with which I began the prologue was never written by Heine. I wrote it myself, and I put Heine's name below it just as I could have put Landru's.

ENRIQUE JARDIEL PONCELA

(This prologue was written under a tent pitched in the heights of Fuenfría (Guadarrama), in August 1928.)

- Action & adventure

- Romance

- Humor & comedy