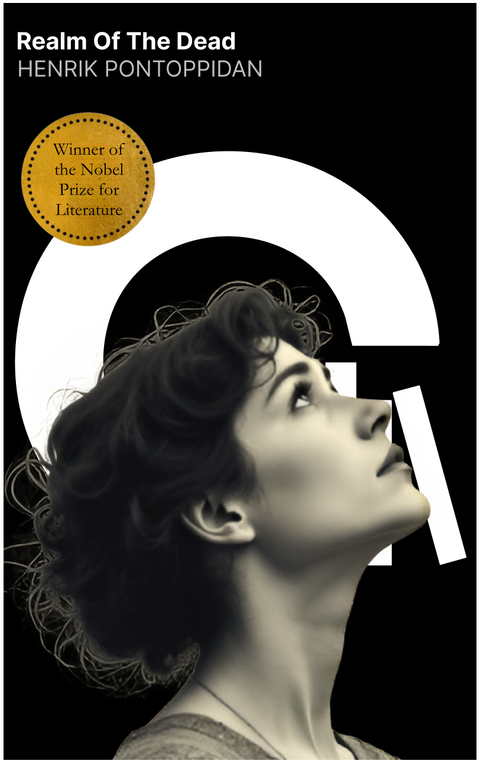

Realm Of The Dead

Read e-books on your Kindle or your preferred e-reader - click HERE to learn how!

Written by Danish Nobel laureate and the father of the modern Danish novel, Henrik Pontoppidan, Realm of the Dead (1912–1916) paints a stark portrait of Denmark in the wake of democracy’s apparent triumph in 1901. Against a backdrop of decaying political ideals, unbridled capitalism, and the corruption of art and the press, the novel delves into the struggles of a young, progressive squire burdened by illness and unfulfilled reformist dreams.

Three years had passed since that September day when young estate owner Torben Dihmer returned home from a foreign spa so ravaged by heart disease that he couldn't get out of the carriage on his own. Two men had to guide him up to his bedroom. On the way there, his eyes rolled back in his head, making everyone think he had died on the spot.

But when he awoke from his faint, he looked around with his kind smile and said, "So I made it home to Favsingholm after all!"

The old East Jutland manor house lay behind an overgrown inlet of the fjord, its red walls and tiled roof reflected in the remnants of a moat. Since his father's tragic death, only the farm buildings had been inhabited. Torben was just a 12-year-old boy without a mother then, and with no siblings, the home was dissolved. He was sent to Herlufsholm School, and in those many years, wind and rain had ruled the castle along with a large staff of rats and mice.

Torben Dihmer came from an old, vibrant family of landowners. In his youth, he had been as strong as a bull calf. His grandfather was Klavs Dihmer, the famous Councillor of State who in the mid-19th century was called the King of the Jutlanders - a sturdy oak of fourteen stone. He drove into Randers in an ordinary farm wagon, but with two beautiful dark brown stallions as his team - the famous Oppenheimers, who well deserved a bronze monument in the town square. They saved the degenerate Jutland horse breed from extinction and opened a new gold vein for the region in hard times.

Torben's father, the Councillor of State, had also been a pioneer in Jutland agriculture. Yet Torben himself broke decisively with family tradition, earning a degree in political science that gained renown, and then traveled abroad to continue his studies and see the world - when misfortune struck him like a poisoned arrow from an ambush.

He wanted to be a politician - a statesman. In politically engaged student circles, he had early on been chosen as one of the future leaders. When his tall, brownish-blonde figure with its careful parting and long ram's face appeared at the podium during debates, the hall fell silent, and not just because of his landowner's title. He was a superior speaker. Among the many youthful hotheads and revolutionary dreamers, he stood out for his almost phlegmatic calm, impressing with his unshakeable objectivity and good-natured humor.

During all that time, he had only stayed at Favsingholm a couple of times for hunting with some merry young friends who rampaged there like a whirlwind for a week or two. Now for three years he sat powerless in his grandfather's big armchair, his hands and feet cold like an old man's, yet unable to die.

But weak as he was, life's restlessness still burned in his mind. Despite his heavy, hippopotamus-like legs, he had to keep getting up from the chair and walk a bit on the floor with his cane to see if he could detect any improvement. Despite shortness of breath and heart palpitations, he was busy all day like a caged animal that, after years of pacing back and forth along the bars, can't give up hope of finding a way out to freedom.

Over in the village parsonage lived a man, Pastor Vestrup, whom he knew from childhood. Twenty years ago, they had briefly sat together on the school bench in Randers and later met again as students in Copenhagen. Torben Dihmer didn't particularly care for him. There was much about the man that irked him. But to hear what the church currently claimed to know about the afterlife, he had once sent for him, and the two childhood friends had since had several long conversations about religious matters, without any saving celestial ladder revealing itself to him over the dark pit of earth that his sick thoughts circled day and night.

It was also bitter for him that even on this side of the grave, nothing would remain of him but a doubtful memory. He had been so carefree about his future, so superstitiously certain of his destiny, and now he sat here having to die empty-handed. It had been written in the stars the hour his mother brought him into the world that his life would pass away and be erased like a wave without leaving the slightest trace.

He still took a daily short walk in the park with his nurse, old Sister Barbara, on whose shoulder he leaned when going up or down the high main staircase. On warm, sunny days, he sometimes ventured all the way to the gate by the haystack area to watch the cattle being driven home to the barn. The workers greeted him with fear in their eyes. He himself was terribly tormented by the monkey business the disease had made of his appearance; and believing the distortion to be more grotesque than it really was, the gates of Favsingholm were kept closed to all strangers. He wanted to see no one.

The once so sociable man had changed greatly. He could have the most unreasonable whims. Sometimes he decided he wouldn't eat, other times that he wouldn't wash. "I can be handsome enough for the graveyard rats," he muttered. He let his hair and beard grow out until it bristled around him like thorny twigs and had now begun to wither and fall off. Similarly, he found a defiant satisfaction in letting everything on the estate fall prey to decay and ruin. "Let it wait until I'm gone," was his stock answer when the inspector or manager proposed some urgent work to maintain the property. "It must end with me someday."

One day in late autumn, unexpected visitors came to the estate. The weather was unsettled, and the sick man had had a bad night.

Professor Hagen had not risen by midday. Old Barbara was in her master's living room adding peat to the fire when she heard a carriage enter the castle courtyard. Startled, she ran to the window. A carriage with its top down, carrying two gentlemen, stopped below the main entrance. She recognized one of them as the doctor from Randers. But who was the clean-shaven stranger sitting beside him? And what did he want here?

"Has Mikkelsen gone completely mad?" she exclaimed aloud when she saw both men exit the carriage and ascend the steps together. Agitated, she hurried to the foyer and told the stranger to his face that he could not enter. The doctor intervened authoritatively, but the old woman stood firm.

"I have my instructions," she said in a peculiar Jutlandic dialect. "You know that very well, Mikkelsen."

"Now listen, Barbara. This gentleman is a Professor of Medicine at the University of Copenhagen - a doctor - and also a childhood friend of the estate owner. Go and announce that Professor Hagen is here. You understand this is an order."

His tone made her hesitate. Her eyes moved suspiciously from one man to the other before she silently led them through the hallway to her master's room. Apart from the dining room and a couple of bedrooms, it was the only habitable space in the large house.

"What on earth is that ghost your dear friend has acquired?" asked the professor when she had gone. "Is that supposed to be a nurse?"

The doctor shrugged. "She's a former night nurse from the area. I've repeatedly offered to find a properly trained hospital nurse, but he won't have anyone else around him. The old simpleton has gained a strange power over his troubled mind. Well, I'll take my leave now. As I said, I have a couple of patients nearby. And the estate owner doesn't appreciate seeing me unless he's explicitly sent for me."

The professor - a small, blond man with a ruddy, childlike face - shook his hand. "I'll send word when I find an opportune moment for a consultation. For now, thank you for accompanying me."

Left alone, he surveyed the large, dark room with its smoke-blackened ceiling, cracked wallpaper, and other sad signs of deliberate neglect and decay. He shook his head. After the new information he'd received from Dr Mikkelsen on the way, it was clear to him that his friend's mental state posed a greater immediate danger than his actual illness. He was glad he hadn't postponed the trip a day longer. Help had clearly arrived just in time.

"You could have answered your friends' letters. Then you'd know more about all of us than I can tell you in a hurry. Do you realize it's been nearly two years since I last heard from you?" Torben nodded.

"Well, that's absolutely unacceptable – as our old headmaster would say. In other words, you've been here forgetting both your friends and your lady friends."

"Of course I haven't. But what was I supposed to write about? I experience nothing but being ill, and that's not an interesting or uplifting topic for healthy people in the long run. I wanted all of you to think of me as deceased – which I am in reality. I thought you had understood that."

"Now listen, dear friend. You're really taking your condition too seriously. Certainly, you're not well, but –"

"Don't strain yourself!" Torben interrupted him. "I'm done for, you know. I've known that for a long time. – And now we've talked enough about me."

The professor fell silent for a moment. Then he began talking again about Copenhagen and mutual acquaintances. As if by chance, he also mentioned his cousin, Jytte Abildgaard; but when he saw how the mere sound of the name made his friend turn his eyes away as if from a sudden, violent light, he quickly changed the subject and asked about his sleep and appetite.

A little later, he said, "I sent you a card the other day to prepare you for my arrival. Did you get it?"

"Yes."

"As you may remember, I wrote that I was coming with good news. Aren't you the least bit curious?"

"Oh, in my position, there's not much that interests me. When Per was hanging in the gallows, his curiosity left him – you remember, don't you?"

"I'm telling you, Torben, you're too despondent. Let me remind you of another old saying: Never let go of hope!"

"That's exactly what I'd prefer to do. It's just miserable cowardice on my part that I haven't long ago ended this misery with a shot of gunpowder. But I'll do it one day."

The last words stuck in his throat. He leaned forward and put his head in his hands to fight back tears.

But now the professor would no longer keep his joyful message to himself. He sat down on the armrest of his friend's chair and put his arm around him.

"Old friend. Listen to what I've come to tell you. ... You should be in good spirits. You've forgotten that we live in a great age, where science – not least my own field – performs a new miracle every day. Your illness is no longer dangerous. In six months, you'll feel completely healthy and strong ... Yes, you're looking at me. But surely you can understand that I'm not saying anything rashly."

Torben, who had raised his head, lowered it again and simultaneously patted his friend's hand that lay on his shoulder.

"I know you, Asmus. You so want to comfort me. But let it be enough now. You know I've done everything humanly possible to get well. I've followed your advice and consulted both Professor Hermann in Vienna and Schinders in Nauheim –"

"Yes, and you've studied old quacks and sorcerers on your own," said Asmus Hagen, tugging at his ear. "You see, I've already ransacked your reading material. But now you should be sensible. Then I'll tell you what has happened."

He stood up, walked across the floor, and began to relate. He had been in Paris in late summer, he said, and had spoken there with the well-known chief physician Dr. de Bèze, who after years of research had now proven that several pathological conditions, which were previously attributed to changes in the heart tissue, were in fact due to destruction of the thyroid gland, which was far less dangerous for the patient. Although the disease was incurable, modern medical science had virtually completely nullified its effects by simply supplying the body with the missing gland secretion in artificial form.

"During rounds, I had the opportunity to examine several of his patients myself and read the journals, and it immediately struck me how similar the entire clinical picture was to yours. And now I must make a confession to you, dear friend. I have since corresponded with our mutual friend Schinders in Nauheim and with your family doctor here, the presumably excellent Doctor Mikkelsen. And now that I've seen you, I don't hesitate to say that I have the best hope of being able to cure you."

Torben, who had a couple of times during his friend's speech waved his hand in violent rejection, had finally become quiet.

"But it's impossible!" he said tonelessly. "I feel it best myself. I'm already a half-decomposed cadaver."

"Nonsense. There's much more life in you than you imagine. But you've treated yourself badly. You've buried yourself in darkness too early, Squire Torben. Who would have thought that of you ... But wait. You can still become the happiest of us all!"

- Drama

- Historical fiction